Gary Oldman interview Playboy (25.06.2014)

(Русский перевод можно прочитать здесь)

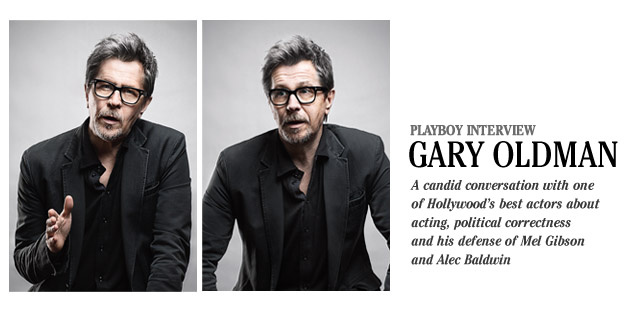

When actors list other actors they deeply admire, Gary Oldman’s name inevitably shoots to the top. Sid Vicious, Dracula, Beethoven, Lee Harvey Oswald, The Dark Knight’s Commissioner Gordon, Harry Potter’s Sirius Black—Oldman’s range is so staggering, a video meme went around recently called “20 Gary Oldman Accents in 60 Seconds.” Google it in awe. He’s Meryl Streep for dudes.

Like all great character actors, the man is less familiar than the roles he plays, which makes sitting down with him intriguing. His films have grossed more than Leo’s, Will’s, Brad’s or Denzel’s, yet Oldman remains as blank as a stare from George Smiley, the “breathtakingly ordinary” British intelligence officer Oldman plays in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. That part earned him a 2012 Academy Award nomination for best actor. This July he leads the human resistance in Dawn of the Planet of the Apes.

Born Gary Leonard Oldman in London on March 21, 1958, he grew up working-class and dropped out of school at 16. His father abandoned the family when Gary was young, but the budding actor later won a scholarship to Rose Bruford College of Theatre and Performance. Acclaim on stage gave way to audacious movie roles, first in the 1986 punk-rock biopic Sid & Nancy and, the following year, in Prick Up Your Ears, in which Oldman plays gay playwright Joe Orton. But it was portraying Oswald to newsreel precision in Oliver Stone’s JFK in 1991 that had critics—and other actors—calling him Hollywood’s best new talent. Life wasn’t always rosy. Years of hard drinking, four marriages (including one to Uma Thurman) and a few behind-the-scenes controversies kept him lying low. Of being famous, Oldman, who has three children, once said, “I haven’t got any energy for it.”

Contributing Editor David Hochman, who last interviewed Jonah Hill, sat down with Oldman over two consecutive days in a suite at the L’Ermitage hotel in Beverly Hills, a venue that stirred certain unchaste memories for the actor (stay tuned). Hochman also discovered that hanging with Oldman is a twofer. “Gary’s longtime manager and producing partner, Douglas Urbanski, sat in with us and hung on our every word,” Hochman says. “If the name sounds familiar, it’s probably from hearing Urbanski on conservative talk radio, where he frequently fills in as a guest host for Rush Limbaugh and Michael Savage. He also plays Harvard president Larry Summers in The Social Network. At first I worried Urbanski might hog the spotlight, but Oldman clearly saw the interview as a rare opportunity to speak his mind like never before.”

PLAYBOY: Let’s begin with an impressive factoid. Based on lead and supporting roles, you are one of the highest-grossing actors in movie history, with films earning nearly $10 billion at the box office worldwide. That must feel amazing.

OLDMAN: I suppose it should.

PLAYBOY: Any working actor would want a career like yours.

OLDMAN: Except me.

PLAYBOY: Wait. You’re not happy with your career?

OLDMAN: It’s not that so much as there’s a perfectionism with me.

PLAYBOY: When you look back at your credits, what makes you say, “I could have done better”?

OLDMAN: Most of it.

PLAYBOY: Really? You don’t like Sid & Nancy?

OLDMAN: I don’t like myself in the movie, no. Frankly, I didn’t want to make it in the first place. I was talked into it at the time. And now, if I flip through the channels and come upon it, it’s “Fuck! Sid & Nancy,” and off it goes. I don’t think I played Sid Vicious very well. I don’t like the way I look in Prick Up Your Ears. I wasn’t the right person to play Beethoven and turned it down half a dozen times.

PLAYBOY: The Dark Knight? Harry Potter?

OLDMAN: It was work.

PLAYBOY: Uh, The Fifth Element?

OLDMAN: Oh no. I can’t bear it.

PLAYBOY: You do realize you’re considered one of cinema’s all-time greats, right?

OLDMAN: It’s all so subjective, you know? I guess I shouldn’t complain. I’ve learned over the years that people get upset when they tell you something is their favorite movie and you go, “Really? You liked that piece of shit?” That’s the sort of thing Sean Penn would say. So I now tell people, “Thank you, that’s great,” and move on. But you know, I remember John Lennon saying that if he could, he’d go back and burn most of the work the Beatles did. He said he’d rerecord all the fucking songs, and I get that. Most of my work I would just stomp into the ground and start over again.

PLAYBOY: Come on. Even Bram Stoker’s Dracula?

OLDMAN: Look, I think there’s been some really good work along the way, good moments. I can look at certain movies and think, That scene was good, or, There’s something I was trying to get at. It was the most thrilling experience watching myself for the first time in JFK, for example, because I couldn’t believe I was in it—Oliver Stone at the very height of his powers, the sheer energy of it all, his commitment. When I saw the finished product I had to pinch myself. I thought, Wow, I’m in this movie. This is terrific. Or to do a role like Smiley in Tinker Tailor and to work with someone like John Hurt, who had been such a towering figure from my younger days. Every day I was like a fanboy. I fainted at his feet.

But I’m 56 now, and if you’ve managed to work as long as I have, you understand that these roles everyone fusses over are your career; they’re not your life. It’s just a job, really. You have financial responsibilities, you have children, you have all those things all the regular people have. Honestly, I forget I’m an actor until I’m reminded.

PLAYBOY: You’re probably not hurting for movie offers. What made you do Dawn of the Planet of the Apes?

OLDMAN: I love the franchise. I was a fan, as we all were, of the original films. I thought the script was very good.

PLAYBOY: And it was a big payday, no doubt.

OLDMAN: Yes, but other big paydays come my way and I go, “Would I want to be part of that? No, thank you.” This one had a pedigree.

PLAYBOY: What’s it like working with a bunch of damn dirty apes?

OLDMAN: Well, it’s hard being around the apes, because they’re basically just actors in weird diving suits with dots on their faces and cameras on their heads. Their mannerisms and facial expressions were ape-like, which was fun to watch. But the finished look comes later, through rendering and special effects. When I did Dracula and Hannibal I spent hours each morning having the makeup glued and strapped to my face. On Dracula the hair alone was a major tribulation. But making Planet of the Apes I had no idea what my co-stars actually looked like. I mean, Charlton Heston was filming with the apes. I used to love those behind-the-scenes pictures where you’d see an ape with a great big cigarette holder or a bottle of Coca-Cola in his hand—that old-time movie magic. It’s not like that now.

PLAYBOY: What’s this sequel about?

OLDMAN: We are 10 or 15 years on from the last movie. The simian flu has pretty much taken care of the world’s population except those who were immune to it. Those who did survive are facing chaos and complete societal breakdown. It’s apocalyptic. I’m a designated leader in the small community of humans trying to reestablish some kind of order to life as it was, having experienced my own personal tragedy in it. It’s a fragile peace between man and ape, and my character is hoping the two factions can co-exist. It’s like putting life back together after Hiroshima or something.

PLAYBOY: It sounds pretty bleak.

OLDMAN: The ultimate message is more hopeful, but yeah, it’s a rather dark view of the future.

PLAYBOY: What’s your view of the future? Are you optimistic about where society is heading?

OLDMAN: [Pauses] You’re asking Gary?

PLAYBOY: Yes.

OLDMAN: I think we’re up shit creek without a paddle or a compass.

PLAYBOY: How so?

OLDMAN: Culturally, politically, everywhere you look. I look at the world, I look at our leadership and I look at every aspect of our culture and wonder what will make it better. I have no idea. Any night of the week you only need to turn on one of these news channels and watch for half an hour. Read the newspaper. Go online. Our world has gone to hell. I listen to the radio and hear about these lawsuits and about people like this high school volleyball coach who took it upon herself to get two students to go undercover to do a marijuana bust. You’re a fucking volleyball coach! This is not 21 Jump Street.

Or these helicopter parents who overschedule their children. There’s never any unsupervised play to develop skills or learn about hierarchy in a group or how to share. The kids honestly believe they are the center of the fucking universe. But then they get out into the real world and it’s like, “Shit, maybe it’s not all about me,” and that leads to narcissism, depression and anxiety. These are just tiny examples, grains of sand in a vast desert of what’s fucked-up in our world right now. As for the people who pass for heroes in entertainment today, don’t even get me started.

PLAYBOY: Well, since you started.

OLDMAN: It’s like the old saying about mediocrity: The mediocre are always at their best. They never let you down. Reality TV to me is the museum of social decay. And what passes for music—it’s all on that plateau. Who’s the hero for young people today? Some idiot who can’t fucking sing or write or who’s shaking her ass and twerking in front of 11-year-olds.

I have two teenage sons and they occasionally turn me on to stuff—Arcade Fire, hip-hop or whatever. I go, “Wow, that’s interesting.” And I do watch television. I’m a huge fan of long-form TV. Mad Men. I loved True Detective; Matthew McConaughey gets better and better. Boardwalk Empire, The Americans, House of Cards—oh God, I loved it. It makes me want to create a show and sit back and get all that mailbox money.

I’m trying to give my sons an education about movies as well. You sit there and watch a comedy, let’s say Meet the Fockers, and it’s Robert De Niro. You tell them this guy was at one time considered the greatest living actor. My boys look at me and say, “Really? This guy? He’s a middle-aged dad.” So what I’ve tried to do recently is introduce them one by one to the great movies of the 1970s—The Godfather, Mean Streets, The Deer Hunter, Dog Day Afternoon, the work of Lindsay Anderson, Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Gene Hackman, Al Pacino, John Cazale, Peter Sellers. I try to give them a sense of what cinema used to be like rather than just these tentpole movies that come and go on demand within five minutes. Don’t get me wrong; there are directors I would still want to work with—Wes Anderson, Paul Thomas Anderson. I’ve never worked with Todd Haynes. I love John Sayles. I’ve never worked with Scorsese.

A great director is a great artist. I felt that way with Alfonso Cuarón on Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. You could just tell being around him that he’s a master, partly because he isn’t afraid to say, “I fucked myself up over here.” I remember a scene where he was scratching his head for two days, figuring out eye lines on 11 characters. “So we’ve got Harry and Hermione looking that way, and now we’ve got Snape, we’ve got Ron, we’ve got Sirius.” Plus he had to match the movements to the mechanical set, which had walls that were moving and breathing. He was never embarrassed to say, “Christ, I’ve really got myself in a pickle here.” And he worked it out. I love it when a director says, “I really don’t know the answer to that.” The thing you don’t want a director to say is “Oh, it’s exactly how I imagined it.”

The best directors are geniuses. I looked up the Playboy Interview with Stanley Kubrick, and it’s remarkable how much knowledge that man had at his fingertips. You need a Ph.D. to understand it. His access to the memory of names—not only could he talk about a theory, but he could talk about what institute the person who devised the theory was from. It’s a great read for a student of cinema like me.

PLAYBOY: Which movie first grabbed your attention?

OLDMAN: To me it was about the actors. It was Malcolm McDowell, Richard Harris, Albert Finney, Alan Bates, Peter Sellers. And Tom Courtenay in films like The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner. But probably the first movie to inspire me was a film directed by Bryan Forbes called The Raging Moon. Malcolm McDowell plays a sort of Cock o’ the North character, a sporting guy, a bit of a lad with the ladies. And he comes down with a paralyzing disease; it may have been polio. He loses the use of his legs and is confined to a wheelchair and gets shunted off to one of those homes where they look after the disabled. I had never been in a school play, but watching that performance was a sort of moment of spiritual awakening when I thought, I want to do that.

PLAYBOY: How did you get into acting?

OLDMAN: We didn’t have any money, but I would generate things. I wanted to learn the piano, so I saved my pocket money and bought a cheap secondhand piano and took lessons. I wanted a guitar, so I saved my pocket money and bought a guitar. I sometimes wish my boys were more like that. Maybe it’s a generational thing. I was interested in performing, so I inquired at school. My math teacher told me about a local youth theater, and I went and met the artistic director. I told him I had this sort of ambition to be an actor, and he said, “Well, you would have to go to drama school, and you would have to have some pieces to audition.” So that would have been the first time I ever really thought about a character. Oddly, it was a Joe Orton character. I didn’t know a thing about him, but I found a speech from Entertaining Mr. Sloane. I was very good at just getting out there. Nothing was handed to me, that’s for sure. My mother did everything she could for me, but I knew I had to do it on my own. I had to escape.

PLAYBOY: What about your father?

OLDMAN: I mean, just google it; it says, “Gary Oldman, son of welder.” When I first arrived in America to promote Sid & Nancy I made the mistake of being overly forthcoming in interviews. I had no rule book. I was so naive. I was very happy where I was in the theater and thought doing a movie would be just a one-off thing. I should have just said, “I don’t talk about family. Next question.” Now, because of the internet and all that, people just go to the fucking morgue, open the drawer and write, “Son of welder, once married to Uma Thurman.” I’m so tired of it. I sometimes fantasize about sitting down in a situation like this and actually saying, “You know, it was all made up. You will never know who my real father was. He wasn’t a fucking welder. I was just having a lark with you all.”

PLAYBOY: Is there something wrong with being the son of a welder?

OLDMAN: It’s not so much that. It’s that your life story is out of your control. [in a nasal voice] “We read many stories after you directed your first film, Nil by Mouth, that said it was autobiographical and that your father used to beat your mother.”

PLAYBOY: And that’s not true?

OLDMAN: No, it’s not true! You’re hearing it from the horse’s mouth. That character is not my dad. My mother never got beat up. That character was a composite—partly fiction and partly a kid I knew at school. It’s not my personal story, but that’s what the media wanted. Sorry, I get a little angry about these things.

PLAYBOY: Your characters are always screaming their heads off. Is rage an issue for you in real life? Are you the guy shouting at the waiter when the food doesn’t come fast enough?

OLDMAN: I know what it means to do a job. I was a sales assistant in several places. I was a stockroom boy and did a lot of sweeping up. I worked in a factory. I respect people in the service industry. What irritates me more is when people aren’t respectful. There’s a lot of nonsense behavior, especially in a place like Hollywood. The money, the power, they create little monsters.

PLAYBOY: If nothing else, you’ve found a profession that lets you channel anger through your characters. The scene in Léon: The Professional of you screaming, “Bring me everyone!” is a classic.

OLDMAN: Again, I could take it or leave it personally. What’s funny is that the line was a joke and now it’s become iconic. I just did it one take to make the director, Luc Besson, laugh. The previous takes, I’d just gone, “Bring me everyone,” in a regular voice. But then I cued the sound guy to slip off his headphones, and I shouted as loud as I could. That’s the one they kept in the movie. When people approach me on the street, that’s the line they most often say. It’s either that or something from True Romance.

PLAYBOY: Another amazing performance. You play Drexl Spivey, a dreadlocked pimp who’s been called the coolest drug dealer in movie history. Please say you enjoyed that role.

OLDMAN: It’s a nice little turn.

PLAYBOY: How did you transform into a white Rasta thug?

OLDMAN: As soon as they told me, “Okay, there’s this white guy who thinks he’s black, and on top of that, he’s a pimp,” I thought, Yeah, I’d like to do that. When you add the matted hair and the eye and the fake teeth, it all comes pouring out. The Drexl voice came to me in New York one day. I heard a kid talking outside my trailer and literally pulled him in from the street and said, “Read this dialogue and tell me what you think.” He read a couple of lines and said, “That’s good, but it don’t fly. I wouldn’t say that.” I said, “What would you say?” and he helped authenticate it so I could show up and become that character.

PLAYBOY: Do people come up and say, “Get off my plane,” like Harrison Ford says to you in Air Force One?

OLDMAN: More than a few times. That movie had some enjoyable moments. I remember the flight deck was on a sound stage and there was a big sign that said NO DRINKING, NO SMOKING AND NO EATING ON SET. At one point I looked over and Harrison was in the doorway beneath the sign with a burrito, a cigar and a cup of coffee, which I thought was hilarious. I could never get the image out of my head. Nowadays we would take out an iPhone and post something like that on Instagram.

PLAYBOY: Let’s talk about directors. How does someone like Francis Ford Coppola, who directed you in Dracula, differ from Christopher Nolan from the Dark Knight trilogy?

OLDMAN: Well, Francis is a hero of mine. He’s arguably the best American director but also a brilliant writer. Many people forget he won an Academy Award for the screenplay for Patton. I recently watched The Conversation again and couldn’t believe how it stands up. I always tell students who want to be writers or directors that first on their list of what to watch should be The Godfather: Part II, because in terms of camera, lighting, cinematography, composition, production design, costume, storytelling, writing and acting, it’s flawless. It’s a master class in filmmaking from soup to nuts.

We didn’t always see eye to eye on Dracula, but I have enormous respect for him. He’s very forceful and lets you know exactly what he thinks. Chris Nolan is more about giving you really good notes. On The Dark Knight he’d do a take and then say something like “There’s a little more at stake.” Francis will shout at you during the take, “There’s more at stake! You love her! No! Love her more than that!” He’s like D.W. Griffith.

PLAYBOY: Goth chicks must have been banging down your door after that movie.

OLDMAN: It’s funny. I used to have this little office on Melrose, and people would come and try to find me. An attractive young woman came in one day with a tattoo of Dracula on her breast and wanted my signature over it. Then she went and had my autograph tattooed. I was cool with that.

PLAYBOY: Have you enjoyed your fair share of groupies?

OLDMAN: I’ve had some wild nights in this hotel, actually. All sorts of goings-on here when I was younger. Hef would be proud of me. I’ve probably had fewer than others but more than some, I suppose. I don’t get the whole autograph thing, though, or taking selfies with somebody. But so be it. People say nice things, though I don’t always particularly believe it. I guess I wish I could enjoy it more. I look in the mirror and think, God, how did I ever fucking make a movie? But there were definitely some wild times.

PLAYBOY: Give us one.

OLDMAN: There’s an amusing story about a trip up to San Francisco fueled largely by vodka and timed perfectly to the big 1989 earthquake. We were literally at the epicenter. Afterward it was like, “Well, was it good for you, darling? Because the earth definitely moved for me.”

Just like anyone out here, anybody in this industry, you’re working with attractive people, you’re young, and one thing leads to another. Few are immune to it. I remember being at a dinner many years ago in New York with Arthur Miller. I was sitting next to him. After we loosened up with a few glasses of vino, I turned to him and said, “Do you ever walk down the street and just stop and go, ‘Fuck, I was married to Marilyn Monroe’?” He went, “Yeah.”

PLAYBOY: Were you loaded on some films more than others?

OLDMAN: It wasn’t that I was at the bar every single night or drinking on set. I always took the work seriously. I always showed up on time. I’m prepared, I know my lines, and I’m shocked when other people don’t. But there was one movie toward the end, The Scarlet Letter, when I was in a dodgy place. And I was pretty good in it too. I have hardly any memory of making it, though.

PLAYBOY: Your co-star Demi Moore called you out on your addiction, right?

OLDMAN: Yes, Demi, lovely Demi. I remain grateful. This past March was 17 years since I last had a drink.

PLAYBOY: What’s the secret to sobriety?

OLDMAN: The secret is you have to want to stop. They talk about 12 steps if you go through the program, but the only one you have to do perfectly is the first, which is to acknowledge that you have a problem and that your life is unmanageable. It’s a horrible thing to be in what people call “the disease.”

PLAYBOY: What’s your take on legalizing marijuana?

OLDMAN: It’s silly to me. I’m not for it. Drugs were never my bag. I mean, I tried it once and it wasn’t for me, though, unlike Bill Clinton, I did inhale. To me, the problem is driving. People in Colorado are driving high and getting DUIs. That’s what I worry about. Listen, if you want to do cocaine, heroin, smoke marijuana, that’s fine by me. It’s just that I worry about kids behind the wheel of a car more than anything.

PLAYBOY: Is there any way the film community could have intervened to save Philip Seymour Hoffman?

OLDMAN: You can try, but you can’t stop someone, no. You have to want to do it for yourself. That’s the only way. I had heard he had run-ins with heroin and booze and things, so it wasn’t a total surprise. Tony Scott committing suicide knocked me sideways. That floored me, as did Heath Ledger. All those ridiculous stories about him being so in the character of the Joker was certainly not the person I knew. That’s sort of ludicrous, people blurring the lines and not understanding. There’s a lot of rubbish talked about acting, and it’s often propagated by practitioners of it. You just want to say, “Oh, shut up.”

Even when you’re working closely with people, you don’t really know what they’re like at home. On the outside someone like Philip Seymour Hoffman appeared to be happy professionally. He had kids; he was working with interesting people. But one never really knows. What eventually happens is you put the drink or the drug before everything else. There’s no argument about how good he was, but who knows what was going on inside? I don’t mean this disrespectfully, but maybe he looked in the mirror and always saw that very pale sort of fat kid. It’s a real tragedy for his family.

PLAYBOY: You’ve been married four times, including, as you mentioned, to Uma Thurman. What have you learned in the process?

OLDMAN: [Groans] Look, relationships are very, very hard. They just are. I mean, four times! I’m not proud to say it. One of them was for 10 minutes. I don’t think it meant very much to either of us. What can I say about marriage? I don’t know. It’s all been a bit of a disaster in that area. I have very good artistic instincts, often right on the money. Love, not so successful. But you know, if someone says, “Here’s a script. Now you’re Beethoven,” that I can do.

PLAYBOY: That was hard work too. You actually played piano for those scenes, right? How did you manage that?

OLDMAN: Well, I do play piano and they showed me playing only certain parts. But yes, I had to learn to play the cadenza to the “Emperor” Concerto, for instance. Just learning that took five hours a day for six weeks. That was the research for the movie, basically—me chained to a Steinway. Whether it’s Beethoven or Lee Harvey Oswald or anyone else from real life, you can’t become the character no matter what anyone says, but with work and research you can go for the spirit.

PLAYBOY: Are you as exacting in other aspects of your life? Is everything color-coded in your closets at home?

OLDMAN: I have very neat closets, yes.

PLAYBOY: Are you meticulous about your car?

OLDMAN: Yeah. It’s part of my curse. I have a Porsche Beck 550 Spyder replica that I look after quite well. The original was made in 1955; mine’s from 1976. And I have a collection of vintage posters. If I get something framed, I can take it back three times to get rid of a little fluff under the glass. I have one of those eyes that I can walk into a room, as I did with my contractor recently, and see the slightest irregularity in a bookcase. I told him, “Yeah, it’s fantastic, but it’s slightly off up there on the left side.” He went, “No, it’s not.” But it was, by something like a sixteenth of an inch. He said, “Fucking hell, how can you see that?”

PLAYBOY: What do you do to relax?

OLDMAN: I couldn’t relax if I tried. I always have to do something. That’s why in my downtime I’m either learning an instrument or doing photography. [holds up hands] I have silver nitrate on my hands because I’ve been working with an old camera I just acquired off eBay—a Dallmeyer plate camera from 1865. I built a little darkroom in the basement, and it keeps me occupied. Keeps me off the streets.

PLAYBOY: How are you with money? Do you micromanage your investments?

OLDMAN: Not really, no. I don’t have a portfolio. I probably have less money than most people think I do.

PLAYBOY: So you’re not seeing much of that $10 billion?

OLDMAN: I mean, I do fine. I once parked my Porsche in George Clooney’s garage while I was away. I said thank you and he said, “It’s no inconvenience. It always makes me look good if I have two Porsches.” You know, that’s what they pay you for. But I’m not getting The Dark Knight or Harry Potter money, certainly. Daniel Radcliffe, now he’s got fuck-you money.

PLAYBOY: What would you do with fuck-you money?

OLDMAN: Well, I sometimes joke that I would just slip away to Palm Springs or someplace and close the gates, find refuge behind the hedges. Right now, for instance, just financing a film, getting studios to part with their money and the sorts of things studios are doing, it’s just a crazy, crazy time. I have a script I’ve written called Flying Horse. It’s about Eadweard Muybridge, the 19th century photographer who arguably invented cinema and had a very interesting life. It’s been nearly two years trying to get money. I have my cast pretty much, but the funding isn’t there. Partly it’s the subject. If it had zombies and Leonardo DiCaprio in it, people would be falling over me.

If you haven’t seen Seduced and Abandoned, you should. It’s a documentary with Alec Baldwin about raising money at the Cannes Film Festival. They try to finance a fictional movie that’s a little like Last Tango in Paris. You see how insane these people are. One guy actually turns to Alec and says, “You were great in that submarine movie. Do you think you could have a scene in this one that takes place on a submarine?” I can understand why someone like Mel, for instance, would finance his own movies now, because it has all become so crazy.

PLAYBOY: Mel Gibson?

OLDMAN: Yeah.

PLAYBOY: What do you think about what he’s gone through these past few years?

OLDMAN: [Fidgets in his seat] I just think political correctness is crap. That’s what I think about it. I think it’s like, take a fucking joke. Get over it. I heard about a science teacher who was teaching that God made the earth and God made everything and that if you believe anything else you’re stupid. A Buddhist kid in the class got very upset about this, so the parents went in and are suing the school! The school is changing its curriculum! I thought, All right, go to the school and complain about it and then that’s the end of it. But they’re going to sue! No one can take a joke anymore.

I don’t know about Mel. He got drunk and said a few things, but we’ve all said those things. We’re all fucking hypocrites. That’s what I think about it. The policeman who arrested him has never used the word nigger or that fucking Jew? I’m being brutally honest here. It’s the hypocrisy of it that drives me crazy. Or maybe I should strike that and say “the N word” and “the F word,” though there are two F words now.

PLAYBOY: The three-letter one?

OLDMAN: Alec calling someone an F-A-G in the street while he’s pissed off coming out of his building because they won’t leave him alone. I don’t blame him. So they persecute. Mel Gibson is in a town that’s run by Jews and he said the wrong thing because he’s actually bitten the hand that I guess has fed him—and doesn’t need to feed him anymore because he’s got enough dough. He’s like an outcast, a leper, you know? But some Jewish guy in his office somewhere hasn’t turned and said, “That fucking kraut” or “Fuck those Germans,” whatever it is? We all hide and try to be so politically correct. That’s what gets me. It’s just the sheer hypocrisy of everyone, that we all stand on this thing going, “Isn’t that shocking?” [smiles wryly] All right. Shall I stop talking now? What else can we discuss?

PLAYBOY: What do you think of the pope?

OLDMAN: Oh, fuck the pope! [laughs and puts head in hands] So this interview has gone very badly. You have to edit and cut half of what I’ve said, because it’s going to make me sound like a bigot.

PLAYBOY: You’re not a bigot?

OLDMAN: No, but I’m defending all the wrong people. I’m saying Mel’s all right, Alec’s a good guy. So how do I come across? Angry?

PLAYBOY: Passionate, certainly. Readers will have to form their own opinions.

OLDMAN: It’s dishonesty that frustrates me most. I can’t bear double standards. It gets under my skin more than anything.

PLAYBOY: Who speaks the truth in this culture, in your opinion?

OLDMAN: There are a number of people. A voice I particularly like is Charles Kraut-hammer. I think he’s incredibly smart. I think he’s fair, very savvy and politically insightful, so I enjoy watching him. There are artists as well, like David Bowie, where there’s an autonomy. He recorded his most recent album and didn’t even announce he was doing it. He was in a position where he thought, Listen, I haven’t produced anything for 10 years. If this is no good, then I can just put it in a cupboard and no one need ever know. But he wrote the songs, picked the cover. I’ve always admired David. I’ve known him about 30 years. We’re friends. And David can constantly reinvent himself because he’s so talented. He has a point of view.

One of my sons wants to be a photographer. I said to him, “Why do you want to rob the bank when it’s already been burgled?” There’s no livelihood there. I know great photographers who are still going around with their portfolios. So I said to him, “Look, I don’t know how you would earn a living, but if you’re passionate and this is what you want to do, boy oh boy, you’ve got to have a point of view. Are you going to be a fashion photographer? Are you going to be a journalistic photographer?” It’s great to just sit there and go, “I just want to take pictures, man,” and fuck off to college for two years that I’ll pay for. Wedding photographer? You need a singular purpose. Can I tell you what else I get frustrated about?

PLAYBOY: Go for it. You’re on a roll.

OLDMAN: More and more, people in this culture are able to hide behind comedy and satire to say things we can’t ordinarily say, because it’s all too politically correct.

PLAYBOY: Do you have something in mind?

OLDMAN: Well, if I called Nancy Pelosi a cunt—and I’ll go one better, a fucking useless cunt—I can’t really say that. But Bill Maher and Jon Stewart can, and nobody’s going to stop them from working because of it. Bill Maher could call someone a fag and get away with it. He said to Seth MacFarlane this year, “I thought you were going to do the Oscars again. Instead they got a lesbian.” He can say something like that. Is that more or less offensive than Alec Baldwin saying to someone in the street, “You fag”? I don’t get it.

PLAYBOY: You see it as a double standard.

OLDMAN: It’s our culture now, absolutely. At the Oscars, if you didn’t vote for 12 Years a Slave you were a racist. You have to be very careful about what you say. I do have particular views and opinions that most of this town doesn’t share, but it’s not like I’m a fascist or a racist. There’s nothing like that in my history.

PLAYBOY: How would you describe your politics?

OLDMAN: I would say that I’m probably a libertarian if I had to put myself in any category. But you don’t come out and talk about these things, for obvious reasons.

PLAYBOY: But there are a ton of conservatives in Hollywood, and libertarians too. Bill Maher has called himself a libertarian.

OLDMAN: I think he would fail the test. Anyway, unlike Bill Maher, conservatives in Hollywood don’t have a podium.

PLAYBOY: Fine. We’ll give you one. What would America look like under President Hillary Clinton?

OLDMAN: What can I say? I feel we need some real leadership, and it’s nowhere in sight. Look at what’s happening right now. John Kerry going off to China to talk about North Korea? What’s that going to do? The ludicrousness of it. What a waste of money. You’re going to go to the puppeteer and say, “Can you help me with the puppet?” As far as Hillary, I guess I feel like my character in The Contender, Shelly Runyon. He doesn’t want Joan Allen to become president; he just believes she isn’t the right person for the job. It’s nothing to do with the fact that she’s a woman, but he uses a bit of dirt on her to bring her down.

PLAYBOY: By the way, what happened on The Contender? The rumor is you objected to the movie’s final cut because it had a liberal bias. What actually went down?

OLDMAN: The stories got blown out of proportion. I just happened to mention that there was another cut of the film that I thought was superior. I can’t even remember what it was because there were so many cuts and things that we watched. But I did watch a cut that was probably a minute and 20 seconds longer that had just a little shift from the final cut that made me go, “I think that’s a better cut than this.” I’m very proud of the film. We produced it. But it had the whiff of a scandal, which I’m told may have cost me an Oscar nomination for best supporting actor. It’s all part of the journey, I guess.

PLAYBOY: Would it mean something to you to win an Oscar?

OLDMAN: I suppose, yeah. But who knows? Does it mean anything to win a Laurence Olivier Award or a Tony? I guess it’s peers or people acknowledging you in some way. I know it certainly doesn’t mean anything to win a Golden Globe, that’s for sure.

PLAYBOY: Why not?

OLDMAN: It’s a meaningless event. The Hollywood Foreign Press Association is kidding you that something’s happening. They’re fucking ridiculous. There’s nothing going on at all. It’s 90 nobodies having a wank. Everybody’s getting drunk, and everybody’s sucking up to everybody. Boycott the fucking thing. Just say we’re not going to play this silly game with you anymore. The Oscars are different. But it’s showbiz. It’s all showbiz. That makes me sound like I’ve got sour grapes or something, doesn’t it?

PLAYBOY: Does it?

OLDMAN: I don’t know. I mean, I don’t have an Oscar.

PLAYBOY: Everyone likes to imagine Hollywood as this glorious monoculture of glittery celebrity, but it sounds as though you feel quite separate from all that.

OLDMAN: I think so, a bit. It’s sort of like a club. I’m respected, but it’s still a little bit like something’s happening over the garden wall. Do you know what I mean? It’s like being invited through the curtain into first class. Occasionally I can see what they eat up there, but then it’s back to my seat.

What people don’t realize is that you need to work at being a celebrity. I’m not talking about movies. I mean the other side of it. You have to campaign. It’s a whole other part of your career, and I wish I could have navigated it a bit better. I may have an Oscar now, had I.

PLAYBOY: Do you consider yourself successful?

OLDMAN: I’m successful. I know that. And I think I’ve been successful because I’m probably very good at what I do. I’ve been very disciplined. I’ve been very focused. I’ve been very lucky—that plays a huge part. Sometimes not getting a role ends up being the best thing. When a project turns out to be a disaster, you look at it and go, “Wow, I dodged a bullet there.” Of course, it’s worked against me when I’ve turned something down and someone had a huge success with it. But it’s been a good run.

I love to work and I wish that could be enough. Now we’re in this thing where everything has to be analyzed and dissected behind the scenes. I personally never want to know how the guy pulls the rabbit out of the hat. I don’t need people prying. Maybe I’m shy. I don’t know. You look at a movie like Hannibal, and even with all that makeup, it was the most free I’ve ever been. I think it’s because I was hidden. On the other side of that coin, the most stressful role, the most painful to do, was Smiley in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. There’s no mask. It’s very exposed. You have to play boring in an interesting way. Not that Smiley is a boring character, but he’s plain. Everything is dialed way down. You look at something like The Professional or True Romance or even State of Grace, and there’s a kinetic sort of ferocity and a fire to those characters, where the volume is up. I understand why Alec Guinness had a kind of nervous breakdown leading up to the shooting of the original Tinker Tailor and wanted out. I had a breakdown too, briefly.

PLAYBOY: You did? What happened?

OLDMAN: At first I passed on the movie, but then I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Once I signed on, I thought, Fuck me! I can’t do this. I can’t pull this off. Everybody’s going to see what a fake I am. This is the moment I get found out. Who does he think he is? He thinks he’s Alec Guinness.

Now, normally I agonize after a movie, not before. I’ll walk down a street and suddenly I’m thinking of a scene I did two years ago. I’ll go, “That’s how I should have done that line.”

Maybe with Smiley I felt that people would see all the things I can see about myself that I don’t like. And if I don’t like them, then they won’t like them. All the things I critique were out there. I remember Peter Sellers saying that the time he was happiest in life was in the very moment of actually playing the characters. Everything else was just a bit of noise—the thought of doing it, the preparation, the building up, the going away, the packing the bags, the getting on the plane, the staying at the hotel. All of that, as glamorous as it sounds, after you’ve been doing it on the road for 30 years, you just want to get on the set and go. It’s like that for me too. Everything is okay when I’m in that moment. As soon as I put the clothes on and walked on the set as Smiley, I was as relaxed as I’ve ever been.